The New New Age

What The Telepathy Tapes says about our search for meaning and the rejection of materialism

Author’s Note: This is the first in a new series of essays I’m publishing under a broader project called The Seeker. If you want more essays like this on consciousness, philosophy, and the nature of reality, subscribe here. Enjoy.

Mia, a 13-year-old Mexican-American girl, waits blindfolded behind a black Mindfold mask. Her mother, Iliana, sits on the other side of a partition. In a small ranch home about ten miles north of downtown Los Angeles, the mother and daughter are part of a strange experiment. Mia is different from most kids her age. Diagnosed a year earlier with non-speaking autism, Mia has never uttered a word.

The experimenter taps a random number generator app on an iPad to load up a new string of numbers. Three random numbers flash across the screen: six, nine, eight. The experimenter shows the tablet to Iliana, who nods to acknowledge she has understood the numbers without speaking. There are others in the room—a documentary film crew and their boss, the show’s creator. They too acknowledge the numbers. They too remain silent. Only Mia is in the dark. Her task is to figure out what numbers her mother and everyone else in the room have seen. The partition slides away. Mia is told to lift her mask and, blinking at the sudden brightness, begins tapping the stencil keyboard in front of her.

6-9-8

When The Telepathy Tapes debuted in December 2024 it cleared two million downloads its first month. By April 2025, it topped fifteen million—and suddenly the culture around us shifted. In the last six months alone, Google linked their quantum computing breakthrough to multiverse theory, Microsoft claimed to have created a new state of matter, and a signature of life on a distant planet (read: alien poop) was discovered. A sitting congresswoman tweeted the Drake Equation shortly before a former senior aide to four U.S. presidents used his final death-bed interview to confirm that “non-human craft are real”, all while serious researchers debate the possibility of discovering Dyson Spheres. As if all this wasn’t odd enough, we’ve also had the White House Science Director quip that the U.S. has technology that can “manipulate time and space.” Things feel different and we’re not even half-way through 2025.

Whatever you think about psychic phenomena1, the public hunger for possibilities beyond strict materialism is undeniable.

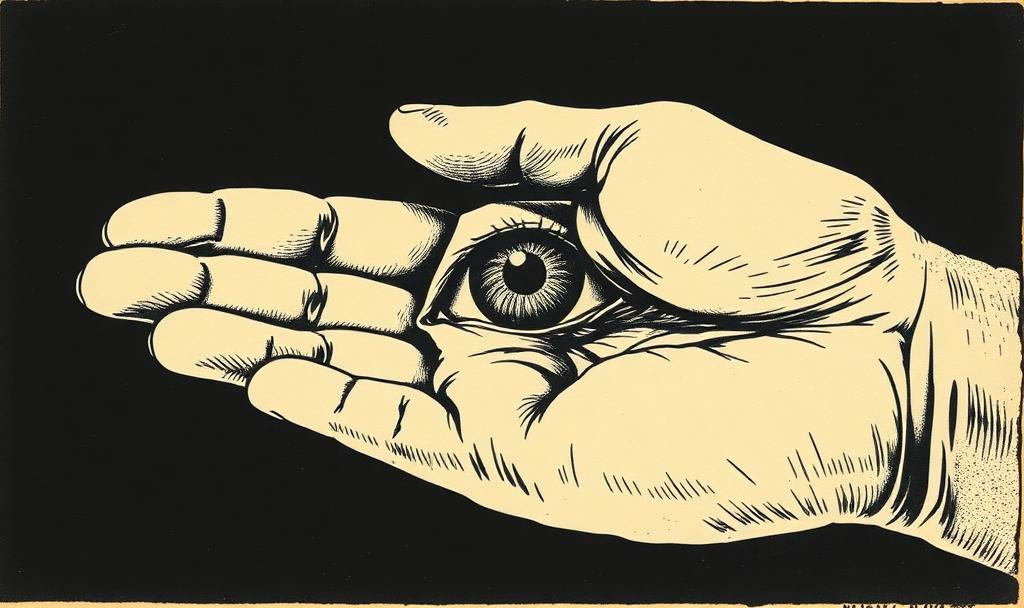

Welcome to the New New Age.

The New New Age

In the late sixties and early seventies, a motley collection of spiritual practices and beliefs coalesced to form the New Age movement. There was no central leader. Not even a real cohesive ideology. It was more of an eclectic mix of ideas and practices—ranging from Eastern mysticism, Hinduism, Buddhism, metaphysics, naturalism, astrology, occultism, and science fiction—that somehow got all smashed together under one umbrella.

If there was one through-line, it was a shared belief that humanity was on the precipice of entering a “new age” of heightened spiritual awareness. This new age would herald in a glorious new moment. One of international peace, an end to racism, poverty, hunger, war, and other social strife. Heaven on earth. Individuals could speed the process up by heightening their own spirituality and “level of consciousness” through meditative practices, altered states, and other techniques borrowed from Eastern traditions or occult practices. There was a sincere belief in a universal connection—a brotherhood of man. “We’re all one,” as the hippies would say.

The new age that adherents anticipated never arrived, or materialized in a form they couldn't recognize. The eighties saw the rise of nationalistic governments and hyper-capitalism. But the end of that decade also saw the end of the Cold War, the birth of new democracies, and an internet explosion that stimulated most of the world’s economies. Things got better globally, just not how the new agers imagined. The rise in living standards and spread of information meant everyone was able to access what once was only found in niche communities. The New Age movement faded not because it lost momentum but precisely the opposite—its core ideas infiltrated the mainstream. By the early 2000s, practices that had been viewed with suspicion by mainstream America were rebranded. Yoga studios, meditation, and self-help books were, at one point, considered fringe. Now they’re in every town across America.

The underlying need for greater meaning never went anywhere. It lay dormant as society, adjusting to a new era of technological advancement, swung in the opposite direction. Then COVID slammed the brakes on all of us. In a way, the pandemic forced many of us to come to terms with what was missing in our lives—meaning beyond traditional structures. Trust in institutions is now at an all-time low. It’s not surprising, then, that 70% of adults identify as “spiritual but not religious,” and a whopping 64% say they believe in “at least one kind of paranormal or supernatural phenomenon”. Younger generations in particular are drawn to this New New Age. And new media voices like American Alchemy by Jesse Michels, Theories of Everything by Curt Jaimungal, The Leading Edge by Tom Morgan, Not Boring by Packy McCormick, and many others are willing to explore, in a serious and open-minded way, phenomena that aren’t easily explainable.

Peeling back the onion, there is a real sense that steam-age materialism might not be the final story. There’s a reason why a decade old declassified government report about remote viewing and podcast documentaries about telepathic kids go viral. The Telepathy Tapes is simply an emblem of this broader cultural moment.

Inside The Tapes

Ky Dickens, creator of The Telepathy Tapes, is an unlikely champion of psychic phenomena. An award-winning filmmaker, she lived most of her life identifying as a science nerd. Dealing with the deaths of two close friends a few years back, she stumbled on a podcast called Cosmos in You, where the guest, neuropsychiatrist Dr. Diane Hennacy Powell, shared her research working with non-speaking autistic savant children who displayed telepathic abilities. Dr. Powell, who graduated from Johns Hopkins and taught at Harvard, also shared how she was stripped of her medical license for the thought-crime of publishing her research in a book about ESP.2 Dickens had an idea. She reached out to Dr. Powell and convinced her to let Dickens bring her research to the broader public. Together, they would travel across the country and record experiments with the telepathic kids to turn it into a documentary.

In each episode, the children stun Dickens, her film crew, and Dr. Powell. The only people not surprised are the parents.

One particular case, a boy named Akhil from New Jersey, nudged me to think there might be something here. Unlike the other kids, his mother, Manisha, has no physical touch with him as he correctly spells what she has not verbally communicated to him.

The skeptical articles and podcasts insist that spelling, or facilitated communication, is a trick. Developed in Australia in the '70s to help non-speaking children communicate their thoughts, it struggled to demonstrate itself in double-blind studies. ASHA discredited spelling as a form of communication, and systematic reviews and controlled studies show the facilitator (often the parent) to be the author. Suggestion, or cuing, can be both conscious or unconscious. If the facilitator knows the answers, there is nothing to prevent the ideomotor phenomenon, i.e. the Ouija board effect.

The Telepathy Tapes provides ample counter-evidence. Eye-tracking tests support evidence of agency and motor planning. Other cited studies show underestimated intelligence, as well as quantitative linguistic evidence that the language produced by individuals with autism via spelling is measurably different from their facilitators’. None of the studies are the holy-grail double-blind tests skeptics say would prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that spelling works. Still, these studies are a big step forward in defending the claim that the communicators might actually be the authors of their own messages. And if they are the authors of their messages, that opens a whole can of unanswered questions. For starters, how in the world are they figuring out what numbers, words, and colors their parents are thinking?

Akhil in particular is a peculiar example. He spells with an iPad he holds—not a letterboard held up for him—and there is no physical touch between him and his mother. Could his mother be using other forms of non-physical cues with Akhil? Sure. She leans back and forth, seems to hum or make sounds, and generally gives positive feedback with each correct stroke. The skeptics say they see patterns of cueing, invalidating the results.

Daniel Engber, Senior Editor at The Atlantic, in his critique of the show said:

If such cuing, rather than the spirit realm, is the source of Akhil’s messages, then one must still acknowledge that he has extraordinary talents. For this mode of spelling to “work” as well as it does, Akhil would need to possess an exquisite sensitivity to his mother’s subtle cues; he’d have to be so attuned to her every gesture and expression, that even chirps and leans and flutters could serve as radar signals, directing him to specific letters on the screen. In other words, he’d need to have special access to his mother’s mind.

This is not telepathy, but it is connection—a connection so intense that I don’t think it would be far off to call it love.

Seth Jordan, at The Whole Social, made an excellent counter-point:

…instead of admitting any possibility that these children might be communicating mind-to-mind, Engber describes them as geniuses at reading social cues. Let me remind you that autistic people are usually regarded as unable to read social cues at all — gestures, facial expressions, and tone of voice are often considered totally beyond the pale… Akhil is able to do this miraculous feat without ever once even looking at his mother.

It’s hard to argue with that.

Skepticism is important, but there’s a difference between skepticism and cynicism.

Dr. Diane Powell had this to say in response to the criticism:

After our experiments the entire sound and camera crew walked away with the same impression [that the children were exhibiting telepathy]. No one visually detected an obvious pattern that could be considering cueing. All told, there were at least ten witnesses, some of whom were filming from multiple camera angles. Nonetheless, the conditions were clearly not optimal for proving telepathy and we cannot definitively say that there was no cueing without more tests and a detailed analysis.

So what would a more optimal testing environment look like? Is there any test that would quiet the skeptics? The answer, unfortunately, is probably not. The reasons are complicated, which we’ll get into. For starters, most skeptics subscribe to a philosophical view of the world known as materialism which rules out anything psychic a priori.

The Dogma of Materialism

Materialism is the predominant view in the scientific community. As Dr. Tony Nader, neuroscientist, medical doctor, and CEO of the Transcendental Movement, explains in Consciousness Is All There Is, physical matter is “the fundamental ingredient of the universe” and consciousness is simply “an emergent property resulting from the organization of subatomic particles, atoms, molecules, cells… into a nervous system and brain that somehow become conscious.” The somehow is important, because there is no conclusion as to how it all happens—and materialism doesn’t state how it happens, just that it does. Materialism is often used interchangeably with Naturalism and Physicalism, though each has its own specific differences and histories. To make things simple, I’ll refer to the catch-all: materialism.

But materialism has also become dogmatic. Researchers who challenge materialism, or posit explanations that fall outside the confines of it, risk being branded with the scarlet letter—pseudoscience. During the Renaissance, it was scientists and philosophers rebelling against the dogmatism of the Church who faced severe consequences (censorship, excommunication, and execution). Today, it is mainstream science and its supporters in the media that have cocooned themselves into their own version of dogmatism, shunning anyone who veers outside.

This is the prevailing idea that leads to harsh pushback by skeptics toward something like The Telepathy Tapes. It is an ideology which starts with an a priori view of how the world must be, so therefore any experience, subjective or otherwise, that does not fit within the mold must be incorrect. Take this article by Sean Carroll for instance. Sean is one of my favorite celebrity-scientist-philosophers. But when it comes to philosophical materialism, his arguments seem dogmatic. He equates psychic phenomena with gravity suddenly reversing tomorrow, suggesting both are equally implausible. This strange (and false) equivalence dismisses the fact that millions of people throughout history have reported psychic experiences, while none, to my knowledge, has ever experienced gravity reversal. What he gets most wrong is presenting his materialist worldview as established scientific fact rather than acknowledging it to be a philosophical position.

If you’re still unsure whether any of this is real, or at least could be real, consider that some of the smartest physicists, mathematicians, psychologists, and philosophers have worked in or adjacent to this field. And while the recent skeptical articles all repeat the same line about parapsychology experiments not bearing any fruit, they aren’t being completely honest.

Ghosts In The Lab

If you only listen to the skeptics, you’ll come away thinking the entire field of psychic research is bogus and made up entirely of crooks and cranks. That’s fair. Many of the smartest people in history recognized the same dangers of parapsychological research and still decided to move forward with it. “No field of scholarly endeavor has proven more frustrating, nor has been more abused and misunderstood, than the study of psychic phenomena,” said Dr. Robert G. Jahn, Dean of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Princeton, at a presentation for the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing in 1979. In addition to his role as Dean of Engineering, Dr. Jahn was also the head of the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR), a parapsychological research program within Princeton University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science that ran for 28 years.

William James, Harvard professor and the father of American psychology, was part of the London Society for Psychical Research and helped found the American version in 1884. The groups were the first systematic effort to organize scientists and scholars to investigate paranormal phenomena. In a letter to his cousin, he claimed that “ghosts, second sight, spiritualism, & all sorts of hobgoblins are going to be ‘investigated’ by the most high-toned & ‘cultured’ members of the community.” He wasn’t kidding. Among the initial founding members were astronomer Simon Newcomb of Johns Hopkins; anthropologist Charles Sedgwick Minot of Harvard; biologist Asa Gray; President of Cornell, Andrew White; and minister Phillips Brooks.

In the 1930s, botanist and professor J.B. Rhine set up a parapsychology laboratory at Duke University. They began publication of the Journal of Parapsychology and published a number of books with their research, but critics and skeptics always found methodological flaws. In one case of experimental dice, where the test subject showed the ability to predict the outcome at a rate greater than chance, it was argued that the dice could be drilled, shaved, or falsely numbered. In every example they set forth of ESP, critics argued that the results were (or could have been) tainted.

Then there’s the Ganzfeld experiments.

The Ganzfeld experiment originated in 1930s Berlin, where psychologist Wolfgang Metzger used uniform sensory fields to study perception. The method resurfaced in the 1970s, notably at New York’s Maimonides Medical Center, where researchers like Charles Honorton adapted it for parapsychology research. Participants would recline in red-lit rooms, eyes covered by halved ping-pong balls, ears filled with white noise, in an effort to reduce sensory “noise” and potentially enhance extrasensory perception.

Jessica Utts, a statistician and professor at UC Irvine, highlighted the Princeton Psychophysical Research Laboratories’ Ganzfeld experiments from the 1980s, which reported a 32.2% hit rate in target identification—significantly above the 25% expected by chance (p = .002). Utts also reviewed later replications and meta-analyses, noting that some found statistically significant results. She emphasized that while some large-scale replications failed, others showed effects that warranted further scrutiny, and she called for more rigorous, independent replication. A recent study reviewed over forty years of research on whether people can sense hidden information under Ganzfeld sensory deprivation conditions. The analysis found a small but consistent effect above chance, especially among experienced participants, suggesting there may be something to the phenomenon, even though it remains subtle and not fully explained.

In her official analysis of the statistical evidence for psychic functioning in U.S. government-sponsored research, Utts wrote: “It would be wasteful of valuable resources to continue to look for proof [of psychic functioning]. No one who has examined all of the data across laboratories, taken as a collective whole, has been able to suggest methodological or statistical problems to explain the ever-increasing and consistent results to date. Resources should be directed to the pertinent questions about how this ability works.”

But if there are no glaring methodological or statistical problems, why do skeptics keep claiming that proof of psi is unfounded? In a word: replicability.

In the the paper Why Most Research Findings About Psi Are False, Thomas Rabeyron, a French clinical psychologist, makes a different claim about the replicability paradox of psi research. “Most research findings in psi research are false (or inappropriate),” Rabeyron argues, “but not for the reasons usually supposed by the skeptics”—but because the way psi might work makes it impossible to test with traditional scientific methods. Psi experiments have an almost existential flaw in that the person doing the experiment (the observer) and the phenomenon being studied (the observed) can never be separated. The experimenter’s intention, the subject’s expectation, even the analyst’s hunch, all might be influencing the results. Try to pin down one source of influence, and another emerges, like a magician’s endless scarves. The explanations multiply, each one plausible, none definitive. This is the Sisyphean fate of psi research: a perpetual ascent, burdened by an infinite regress of maybes and what-ifs, in which every attempt at certainty only deepens the uncertainty. Instead of answers, we get a hall of mirrors, and each reflection suggests, with a certain Gallic shrug, that the truth remains just out of reach.

To be clear, replicability isn’t unique to psi research. The replication crisis of the last two decades has shown issues across the social and applied sciences, including psychology, medicine, nutrition, economics, and water resource management. In 2016, Nature magazine asked over 1,576 scientists for their thoughts. Over 70% said they failed to reproduce another group’s experiments.

The Physics of Consciousness

David Kaiser’s How The Hippies Saved Physics tells the (true) story of a group of young counterculture physicists in 1970s Berkeley. Calling themselves the Fundamental Fysiks Group, they helped revive interest in Bell’s Theorem at a time when mainstream physics was largely ignoring its implications. They also did lots of LSD and tried to find overlap between Eastern mysticism and quantum physics. Despite their eccentricity, their work eventually led to the formulation of quantum information theory, which directly impacts recent advancements in quantum computing.

Saul-Paul Sirag was one of its members. A theoretical physicist and mathematician known for exploring the connections between consciousness, hyperspace, and the foundations of physics, he supported the possibility of telepathy by proposing that all individual consciousnesses are interconnected projections from a greater cosmic mind or hyperspace. In his view, telepathic experiences are natural outcomes of our shared origin in this unified field of consciousness, and may even be accessible or explainable through the mathematics of higher dimensions and modern physics.

Today, consciousness studies is a much wider and more respected field of research. There are voices like Donald Hoffman, who argue that space and time are not fundamental and that consciousness—not matter—is primary. Physicist and science writer Anil Ananthaswamy explores models where the observer plays a constitutive role in reality, drawing on quantum foundations. Neuroscientist Christof Koch, once a strict materialist, has shifted toward panpsychist interpretations. Nobel laureate in physics Roger Penrose and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff developed the Orch-OR (Orchestrated Objective Reduction) theory, suggesting that consciousness arises from quantum processes inside neuronal microtubules3. And thinkers like Bernardo Kastrup are attempting to ground idealism in analytic philosophy and cognitive science.

Sirag anticipated this drift decades ago, insisting that physics would need to expand its ontology to make room for mind. This is not to say that any of the modern-day consciousness researchers are proponents of telepathic or psychic abilities, but they do share Sirag’s core instinct: that consciousness is not an emergent property of brain matter, but a fundamental feature of the universe, best understood through the lens of quantum physics. And most importantly, they are shifting the Overton window beyond what strict materialism allows.

A Different Kind of Knowing

Maybe Mia and Akhil were guessing. Maybe it was all their parents directing their selections. What matters is not what this story says about them, but what it says about us. About how little we understand of the mind, and how quickly we are to explain away answers that don’t seem to fit.

For over a century, the scientific community has drawn a line around what counts as real. Psi, telepathy, and consciousness that doesn’t reduce to simple neurons have been pushed outside that boundary. And yet, we keep looking.

It’s easy to dismiss belief in telepathy as a symptom of magical thinking. Harder to ask why so many intelligent, skeptical people still find something in it worth exploring. The most difficult thing, though, may be the fact that our current model of reality doesn’t explain the most basic fact of our existence: our subjective experience.

We keep insisting on the map’s accuracy while ignoring the territory in front of us. If nothing else, The Telepathy Tapes reminds us that mystery still exists.

My personal opinion on whether psi-phenomena, or “psychic abilities”, is real or not is that while I am not 100% convinced I am increasingly open to the idea. A psychic agnostic.

Dr. Hennacy Powell was later re-instated after the board agreed in arbitration that her experiments were rigorously sound, though the damage to her reputation remained. Dr. Powell is now retired from practicing medicine.

A reader noted that the Orch-OR theory, developed by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff, does not claim that consciousness originates in the brain. Rather, it suggests that proto-conscious events are constantly occurring across the universe, and that microtubules in the brain may uniquely structure and amplify those events into sustained, coherent awareness. The original phrasing has been left unchanged for readability but may oversimplify the model.

"So what would a more optimal testing environment look like? Is there any test that would quiet the skeptics? The answer, unfortunately, is probably not."

I do agree that people are attracted to TTT etc because materialism is not satisfying to people. I think, in our current atmosphere of political chaos, people also want something magical that offers a hope beyond what we can imagine from material solutions.

And while I'm not skeptical about a transcendent quality of consciousness/reality (I, too, have had unexplainable experiences), you hardly have to be "a skeptic" to be reasonably confident that the TTT recorded "tests" are bunk on their face. And an "optimal testing environment" would be extremely easy to achieve:

- Make sure Akhil cannot see or hear his mother when she "sends" him messages.

- Same with Mia -- and don't let her mother literally shove her head in the direction of the correct popsicle stick.

- And for the kids who are using spelling boards, put the boards on stationary stands so that facilitators can't put them in various positions or move them around while the kids are choosing letters.

These are not difficult nor unreasonable protocols, and they would quickly negate the seemingly obvious explanations of how physical communication, not psychic, is taking place between the kids and facilitators.

The easy cope is to say "no, no, even if we do that it won't be enough." Or as others say, "but the telepathy depends on vibrational energy that would be lost under these conditions."

I believe this is because people think in terms of abstract association and tribalism. They associate these wonderful kids with something magical and hopeful, or with their existing beliefs about spirituality/consciousness. To deny the reality of the kids' psychic phenomena is to deny (or threaten) something much more, which people naturally resist.

And anyone who calls for alternative explanations? They are enemies of the believers' deeply held beliefs and feelings, and need to be written off. The easy way to do that is to categorically claim they're all just stubborn materialist reactionaries who could never believe in anything paranormal in the first place -- so don't bother with them.

Meanwhile -- no one gives af about the kids, really. No one cares that they might be exploited, that these exploitations might lead to more kids getting exploited. That other parents will sink hours and emotions into some project to get their own autistic children connected to the "field", only to be disappointed when it doesn't work. "I guess my child isn't special like those others."

It's disturbing on multiple levels. Especially when you scale this out. Next it will be "conscious" A.I. with psychic powers. And all along, people will be increasingly conditioned to simply brush away any skepticism. It creates a breeding ground for cults, paranoia, delusion -- all in a time when people are going to be increasingly looking for some kind of religious or spiritual truth to offer stability in an increasingly chaotic world.

And its a shame because the religious/spiritual impulse is important and valid. And there are ways for spirituality to be held without needing to turn a blind eye to critical thinking and the wellbeing of children. But here we are. Because our culture has nothing better to offer.

I’ve had two dogs that were definitely psychic. They were both able to read my mind. Doubters claimed I was giving them signals but if that were the case the signals were totally unconscious on my part, and the circumstances were not conducive to signals of any kind.